Friday 1st August 2025

“I’ve been to hell and back. And let me tell you it was wonderful.” – Louise Bourgeois

Recently, I’ve been thinking about secrets, particularly childhood whisperings or hushed tones from behind closed doors, which, when untold, tend to fester until they become monsters that make us act in strange ways, tell us not to trust, not to breathe too loudly.

Watching the film adaptation of Deborah Levy’s novel Hot Milk led me to wonder, is it possible for untold secrets to manifest themselves in the body as well the mind and if so, how may this trauma be passed onto the other bodies it comes into contact with?

Hot Milk tells the story of Rose, who has come to Spain with her daughter Sofia to seek a cure for Rose’s disabling chronic pain. As the narrative unfolds, the audience becomes aware of a secret, a burden which, as untold, has spiralled to infect each life that it touches.

Louise Bourgeois is referenced subtly throughout the film. The artist’s work explores trauma, the maternal body and memory all of which are central to the film. We are led to analyse the relationship between physical and psychological trauma manifested in the work of Bourgeois and how this relates to the characters in Hot Milk.

The Body in Pain – Trauma as Physical Manifestation:

Cell installation with Spider, Louise Bourgeois 1997

Rose’s mysterious paralysis serves as a symbol of how trauma can manifest in the body, blurring the boundaries between physical illness and psychological distress. Her refusal to commit to a clear diagnosis, paired with her dependency on her daughter Sofia, suggests that her condition resists medical certainty because it is rooted not in biology but in memory .

According to Freudian theory, the ‘hysteric body’ refers to a physical manifestation of psychological distress often through unexplained symptoms like paralysis or pain. Historically, hysteria was considered as an illness that affects mainly women from upper social and economic class, we are reminded of Virgil’s Dido who commits violent suicide as a result of her trauma or Shakespeare’s Ophelia. While often stereotyped as an imagined illness for unstable women, Freud viewed hysteria as a serious psychological illness seen in men as well as women and rooted in the repression of unpleasant emotions that caused by a traumatic event in a patient’s life.

This idea of the body as a vessel for repressed pain is echoed in the work of Louise Bourgeois, whose words we see at the beginning of the film “I’ve been to hell and back. And let me tell you it was wonderful.” For Bourgeois, suffering is not just something to be endured but something to sculpt and channel into spatial forms that give presence to the otherwise invisible. In a 2007 e-mail exchange with the Los Angeles Times, she shared that her art was “a form of psychoanalysis” which gave her access to the depths of her unconsciousness and a means of exorcising pain which constituted her “guarantee of sanity.”

Her Cell installations which feature cage like structures, fragmented torsos, and Arch of Hysteria speak to this process of externalising internal states. Despite being a self proclaimed ‘hysteric’ Bourgeois rejected some of Freud’s core theories, particularly the idea that psychoanalysis could cure an artist’s torment. Instead she believed that the suffering inherent in artistic creation was not something to be eliminated, but rather a driving force behind her work. According to art critic Christopher Turner, Bourgeois saw her art as an ongoing process of exorcising personal trauma, not as a means to achieve a state of cure. Like Rose’s paralysis, Bourgeois’ bodily sculptures suggest that trauma does not vanish but instead finds alternative routes through the body – through illness, gesture, or material. These psychosomatic symptoms become narratives in themselves, speaking what cannot be spoken.

Generational Trauma – The Mother-Daughter Dynamic:

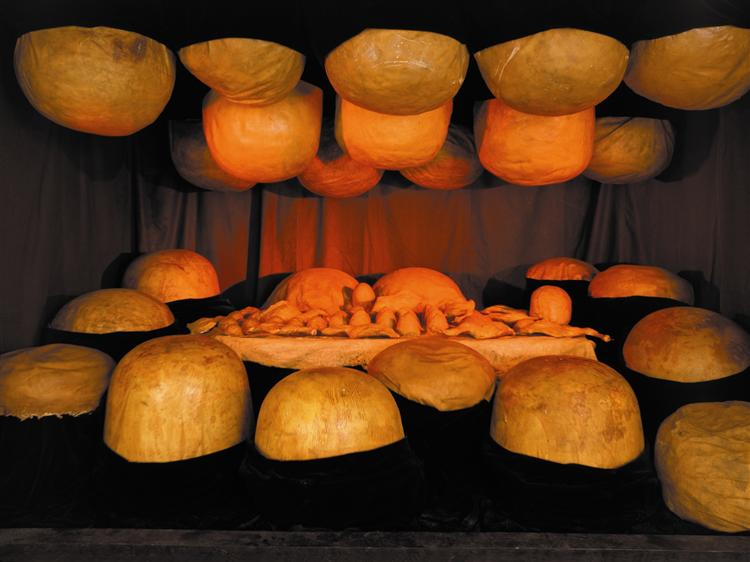

The Destruction of the Father, Louise Bourgeois 1974

We see the links between Bourgeois’s work and Hot Milk elsewhere in the relationship between Rose and her daughter, Sofia. As Sofia acts as both caregiver and reluctant witness to her mother’s mysterious illness, her own life is held in suspension; her subjectivity becomes secondary to Rose’s bodily needs and emotional volatility. Unspoken grief, regret, and resentment quietly circulate.

This dynamic echoes Louise Bourgeois’ persistent exploration of the mother-daughter bond as a site of psychic tension and unresolved pain. In works like Femme Maison, the female body is fused with the architecture of domesticity, implying entrapment and erasure – much like Sofia, who is confined within the invisible architecture of her mother’s suffering. We see that even without knowing the details of her mother’s suffering, the secret is passed on and inhabits Sofia’s body leaving her uncertain of her own place in the world.

Meanwhile, in The Destruction of the Father, Bourgeois reconstructs a childhood scene of rage and repressed emotion, translating the familial into a grotesque, visceral tableau. For Bourgeois, trauma is not only remembered – it is relived through material, suggesting that the past is never truly past but instead inscribed into form and flesh. Similarly, Rose’s trauma – unnamed but ever-present — is not told to Sofia directly, but enacted and inhabited, shaping Sofia’s own relationship to her body, identity, and freedom. Theirs is not just a bond of care, but one of haunting.

Hot Milk ends somewhat unexpectedly, offering no comfort in the truth. Neither the film nor Bourgeois’ work offers a clear ‘cure’. Instead, they expose trauma, making it visible and legible. Louise Bourgeois’ work seems to provide a framework for the film’s narrative and a mirror for Sofia to understand her own relationship with her mother. We see that healing may lie not in medicine but in confronting the past, questioning and giving shape to the unspeakable.